The First Grail Romances

Robert de Boron's account was the third of three key texts that had a major influence on the tradition of the Grail we know today. The first known literary account of the grail was produced by Chretien de Troyes writing around 1180 AD. Chretien is credited with writing five Arthurian Romances, his last, Perceval, or le Conte du Graal, the Story of the Grail, was his last last work and, for whatever reason, left unfinished. In Chretien's original work he simply described the object as 'a grail' (un graal), a serving dish. Chretien describes the Grail as part of a mysterious procession that started with a squire carrying a lance bleeding from its tip, then two squires entered with candelabras of 10 candles each followed by a maiden carrying a 'grail' from which such a brilliant light radiated from it, so bright that the light of the candles faded like the stars when the sun or moon are rising.1 Alternatively, the light may have been coming from the maiden herself.2

Chretien tells us little else about the mysterious objects of the grail procession, omitting to tell us it is the cup of the Eucharist and at no time connects it to the relics of the Passion. Surely the attraction of Chrétien's grail was that neither he nor his audience knew exactly what it represented; yet both seem to realise the importance of witnessing the procession. A suspected later interpolation into the Conte du Graal adds that the grail sustains the Grail King with a single mass wafer. The same hand is probably responsible for naming the lance as the weapon used by Longinus at the Crucifixion that pierced Christ's side in the First Continuation.3

The second great Grail Romance was penned by Wolfram von Eschenbach, a German knight and poet, in the first quarter of the 13th century following shortly after Chretien's work. In Wolfram's introduction to his Grail epic Parzival he claimed that Chrétien's version of the tale had failed to present the true story of the Grail and states that his source was a poet from Provence called Kyot. To Wolfram the Grail (Gral) is a heavenly stone, the lapsit exillis, an emerald from Lucifer's crown that fell to earth, with the names of those appointed to the Gral inscribed on its top edge, but as soon as the name is read it vanishes from sight. It is tempting to speculate exactly what Wolfram had in mind; his lapsit exillis may simply be a corruption of lapsit ex caelis meaning the 'stone that fell from the sky' but of course it also brings to mind the lapsis elixir, the stone of the wise, the Arabic term to describe the Philopsher's Stone or the mythological tradition of the Emerald Tablets of Thoth etched with mystical writings. However, in transforming Chretien's serving dish to a stone from heaven Wolfram diverged from most other Grail Romances.4

When he finally arrives at the Grail Castle, Perceval seeks initiation into the Brotherhood of the Gral. His initiation occurs in two stages: on two occasions he will appear before the Gral; the first time he will fail the trial.

Wolfram describes a procession similar to Chretien's account where the bleeding lance and the Gral with the addition of ivory trestles and glass vials in which balsam was burning, are paraded in front of him by twenty four maidens. Then the twenty-fifth maiden enters bearing the Gral, whereas in Chretien she is unidentified, Wolfram tells us this is the princess of perfect chastity, Repanse de Schoye, and again as in Chretien, she radiates a brilliant light: “her face shed such refulgence that all imagined it was sunrise.”5

Later, Parzival is told about the Gral, how a warlike company of Templars, the Brotherhod of the Gral, dwell at Munsalvaesche (the Grail Castle). They are nourished from the Stone, the lapsit exillis, who's essence is pure. No matter how ill a mortal may be he cannot die for a week after seeing the Stone. The Gral is nourished by a Dove from heaven on every Good Friday which delivers a small white Wafer to the Stone that it leaves there.6 In a Christian context this may be interpreted as a reference to the former practice of reserving the Blessed Sacrament in dove-shaped receptacles (columb) suspended by chains from the canopy of the altar.

According to Chretien and Wolfram the Grail clearly possesses some religious significance, the procession is an initiation rite, but it is not to linked to the Christian rite of the Eucharist.

The Christianisation of the Grail

Robert de Boron wrote two poems at the beginning of the 13th century; the Joseph d'Arimathe and the Merlin, the latter work surviving only in fragments; the first writer to make a connection between the legend of Joseph of Arimathea and the Matter of Britain. These two works are thought to have formed a greater opus, Le Roman de l'Estoire dou Graal, with the Perceval forming the third and final part. It is likely that de Boron's final work is represented in the Didot Perceval, thought to have been written between 1190 to 1215 AD. The Didot Perceval survives in two quite dissimilar texts in two manuscripts known as the Didot (Paris) and the Modena variants. In both manuscripts containing the prose Perceval it is preceded by a prose version of the poem Joseph d'Arimathie by Robert de Boron and by a prose Merlin, a re-handling of the poem by de Boron. The prose Perceval may be the work of a continuator of the two compositions of Robert de Boron and may bear some resemblance to the lost original.

The Joseph d'Arimathie provides the first history of the Grail but does not mention the bleeding lance but it appears later in the Didot Perceval which follows Chretien in the Grail Procession: “Just as they seated themselves and the first course was brought to them, they saw come from a chamber a damsel very richly dressed who had a towel about her neck and bore in her hands two little silver platters. After her came a youth who bore a lance, and it bled three drops of blood from its head; and they entered into a chamber before Perceval. And after this there came a youth and he bore between his hands the vessel that Our Lord gave to Joseph in the prison...”7

Later in the tale the Fisher King explains the mystery of the Grail to Perceval: “Dear grandson, know that this is the lance with which Longinus struck Jesus Christ on the cross, and this vessel that is called the Grail, know that this is the blood that Joseph caught from His wounds which flowed to the earth....”8

The Didot Perceval closely follows Chretien's account but for one major detail; the Grail is carried by a youth rather than a maiden. This is further evidence that Chretien did not intend his grail procession to be symbolic of the Eucharist. Why did de Boron change the gender of the grail bearer?

The supposed ‘ritual uncleanness’ of women during these times led to many prohibitions in Church Law and it was strictly forbidden to have women serving near the altar within the sacred chancel and they were prohibited from entering behind the altar rails during the liturgy. Only men and boys could serve at the altar. The presumed ‘ritual uncleanness’ of women entered Church Law at the time of the flourit of the Grail Romances especially through the Decretum Gratiani (1140 AD), which became official Church law in 1234 AD, a vital part of the Corpus Iuris Canonici and remained in force until 1916.

Women could not distribute communion, teach in church, baptise, wear sacred vestments and they certainly could not touch sacred objects. It was not until 1983 that canon 230 of the Code of Canon Law allowed local ordinaries to permit girls and women to serve the altar and touch sacred objects. If Chretien's grail had been intended as the Chalice of the Last Supper the Grail procession in his tale would have been regarded as Liturgical Abuse. In making the Grail an object of Christian veneration de Boron had no choice but to change the gender of the Gail bearer to a male.

de Boron's work was the inspiration for the Grail Romances that followed and spawned the huge Vulgate Cycle. He was the first author to provide a complete history to the Grail and the first to give a Christian dimension to the legend, relying heavily on the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. According to de Boron, the Grail was the vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper and then used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch the Holy blood at either the Crucifixion or the Deposition. While imprisoned Joseph was sustained by the Grail and the true meaning of the cup was revealed to him by Christ himself. Joseph's family then brought the Grail to the vaus d'Avaron, the valleys of Avaron, in the west, interpreted by later writers as Avalon and subsequently identified with Glastonbury. The mention of Avalon has fuelled the argument that de Boron wrote his work after the monks of Glastonbury had discovered the grave of Arthur and Guinevere in the Abbey grounds in 1191; the inscription on the burial cross confirming that the place was indeed Avalon.9

The legend of Joseph of Arimthaea was generally known at the time with various rhymed French versions in circulation, whereas the Gospel of Nicodemus was used by Gregory of Tours in the 6th century and later translated into Anglo-Saxon, French, English and German in the 12th and 3th centuries.10 Joseph of Arimthaea was particularly venerated at Moyenmoutier in Lorraine in north east France, across the Vosges mountains from Montbeliard and the nearby village of Boron, the apparent birthplace of Robert, which may have influenced his selection of material.11

At one time the Abbey of Moyenmoutier claimed to possess the relics of Joseph of Arimthaea. According to the early 13th century Chronicles of Senones during the time of Charlemagne (king of the Franks 768 - 814 AD), Fortunat, patriarch of Grado, made a pilgrimage to the East and brought back the body of Joseph of Arimathea from the Holy Land to the monastery of Moyenmoutier. At a later date, but before the end of the 10th century, the body of Joseph was taken away by 'strange monks.'12 Although this is a late tradition it may have contributed to the persistence of the Glastonbury tradition whose monks were suspected of the crime.13

In Chretien's story de Boron seems to have recognised elements of the Grail procession as relics of the Passion; the Holy Lance of Loginus and the Chalice bearing Christ's blood as the cup of the Last Supper. Yet it is doubtful that this is what Chretien intended for his unfinished story of the grail. Key to de Boron's thinking must have been the recognition of the Grail Maiden bearing the chalice in the Grail Romances as Ecclesia a figure depicted in Christian iconography as the person holding the chalice and catching the Holy Blood at the Crucifixion in illuminated manuscripts, for which, as we have seen above, he substituted a youth. There is evidence that the Grail legend, at least in the form of the Chalice at the Cross, was known in the Rhine regions from at least the early 6th century.14

The First Grail Maiden

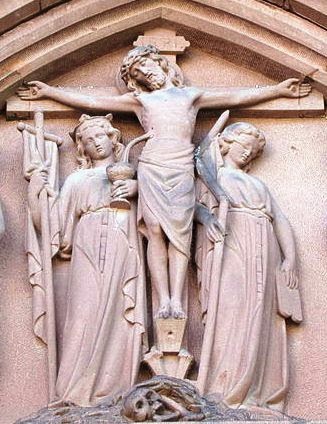

Ecclesia usually appears with Synagoga in Crucifixion scenes from the early 9th century. Ecclesia is shown receiving the Holy blood in the chalice on the 9th century ivory cover to Henry II's early 11th century book of Pericopes. Ecclesia is said to represent the new church as the Virgin, Mary The Church, and is often depicted in Crucifixion scenes with a blindfoled female companion who's head is bowed standing on the opposite side of the cross bearing a broken lance and holding law tablets that are slipping from her grasp. This figure is said to depict Synagoga, the Synagogue, the Jewish Church that turned its back on Christ at the Crucifixion.

However, the earliest depiction of Ecclesia is from the beginning of the 5th century where she is shown as a veiled woman offering a wreath to St Peter while another figure of her crowning St Paul in the apse mosiac at Santa Pusenziana in Rome dated c.400 AD.

The Gellone Sacramentary, dated 790-804 AD, has a Crucifixion scene showing a bleeding Christ without any earthly attendants, a scene which does not appear to have any precedents and was done perhaps to avoid distracting from the scene on the opposite page. This page (folio 144r) represents a head with long hair, forming the top of an initial I for the section of Te igitur that begins Inprimis quae which asks for blessing on the church. In this context the head may represent Ecclesia.

The 8th century Gellone personification seems to be without precedent and predates both the 9th century Utrecht Psalter and the Drogo Sacramentary, the latter showing an unmistakable depiction of Ecclesia catching Christ's blood in a chalice which is possibly the earliest depiction of this theme.

In the Utrecht Psalter depiction of Psalm 115 is the first in the West of Christ hanging dead on the cross. To the left are Mary and John, to the right a mysterious male figure in a loin-cloth holding a paten with bread in his right hand and in his left the chalice held to Christ's side. These images are unique to the Ultrect Psalter, Other psalters of the period such as the Stuttgart Psalter, c.820 AD, do not show this.

The unidentified figure receiving blood in the chalice appears only in the illustration to Psalm 115, folio 67 recto illustrating Psalm 115 verse 4: "I will take the chalice of salvation and I will call upon the name of the Lord" which was recalled during the Mass liturgy. This may be the earliest extant use of this image and earlier than the first depiction of Ecclesia at the Crucifixion scene and is the only scene in the Psalter with an overtly Eucharistic reference, connecting the chalice to the cup of the First Mass.15

It is therefore without doubt that the maiden collecting Christ's blood in a chalice at the Crucifixion is intended as the Chalice of the Eucharist and in this Robert de Boron saw the Grail Maiden of Chretien's Conte du Graal. But what is the significance of the Grail bearer being a virgin?

The Virgin and the Grail

Representations of the Virgin Mary holding a chalice are to be found in the Pyrenees mountains of north west Spain. Some fifty years before Chrétien de Troyes wrote the first known story of the Grail, images of the Virgin Mary with a simple bowl (called a “grail” in local dialect) containing radiant red blood appeared in St Clement, Taull, and eight churches in the Spanish Pyrenees. Historian Joseph Goering argues that they were the original inspiration of the Grail legend, in his view these wall paintings are "the historical origins of the Grail."16

In early 12th century Catalonia the church of St Clement was visited by the master painter who made beautiful frescoes of Christ in Majesty and seated with the apostles is an enigmatic representation of the Virgin Mary holding a Grail, a shallow bowl exuding radiant light, perhaps so hot she covers her hand with her cloak. Other churches in the Catalonia region had similar pictures (and in one case, a damaged statue) with this Grail motif that is found nowhere else in Christendom. The first was commissioned at St Clement in 1123 AD, these paintings bearing testament to the existence a local tradition, or cult, some fifty years before the earliest date for Chretien's Conte du Graal. To add to the mystery of the Grail, in these paintings the lips of the Virgin (Sancta Maria) are shown stitched together as if sealed to safeguard some great secret.17

In one painting from the main apse of St Peter of El Burgal the Virgin is seated next to St Peter and She is holding a ciborium, of similar construction to the Chalice of Dona Uracca, with a central container mounted between two cups or bowls, the lower one inverted to form the base. The ciborium from St Peter's, as with all other representations from these nine churches in the Catalonia region, emits a radiance from the blood within.18

In can be of little coincidence that the Grail romances appeared just as Eucharistic devotion was gaining favour at the same time as the recovery of relics of the Passion from the Holy Land became the driving theme of the Crusades.

In addition to its use at the Last Supper, the cup of the First Mass, the Holy Grail was said to have been used to catch the blood of Christ at the Crucifixion. The “Chalice at the Cross” motif that had emerged at the end of the first millennium showing the Chalice in the hands of Ecclesia as the first representation of the Grail Maiden was in existence several hundred years before the first Grail Romances were written.

Copyright © 2014 Edward Watson

http://clasmerdin.blogspot.co.uk

Notes & References

1. William Kibler and Carleton Carroll, trans. Chretien de Troyes: Arthurian Romances, Penguin Classics, 1991.

2. DDR Owen, The Evolution of the Grail Legend, University of St Andrews, 1968.

3. Ibid.

4. Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival, trans. A. Hatto, Penguin Classics, 1980.

5. Ibid p.125.

6. Ibid p.240.

7. Dell Skeels, Didot Perceval or, The Romance of Perceval in Prose: A Translation, University Of Washington Press, 1966. >> Mary Jones Celtic Literature Collective.

8. Ibid.

9. Nigel Bryant, trans. Merlin and the Grail: Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, Perceval: The Trilogy of Arthurian Prose Romances attributed to Robert de Boron, D.S.Brewer, 2008.

10. Emma Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz, The Grail Legend, Princeton University Press, 1998.

11. Ibid.

12. John Matthews, ed. Sources of the Grail: An Anthology, Floris Books, 1996, p.351.

13. Emma Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz, p.344 (fn.15).

14. Linda Malcor, The Chalice at the Cross, 1991.

15. Ian Levy, Gary Macy, Kristen Van Ausdall, editors, A Companion to the Eucharist in the Middle Ages, BRILL, 2011.

16. Joseph Goering, The Virgin and the Grail, Yale, 2005.

17. How else would you paint sealed lips? – see Urgell and the Holy Grail.

18. Goering, op cit.

|

| Grail Maiden - Arthur Rackham 1917 |

When he finally arrives at the Grail Castle, Perceval seeks initiation into the Brotherhood of the Gral. His initiation occurs in two stages: on two occasions he will appear before the Gral; the first time he will fail the trial.

Wolfram describes a procession similar to Chretien's account where the bleeding lance and the Gral with the addition of ivory trestles and glass vials in which balsam was burning, are paraded in front of him by twenty four maidens. Then the twenty-fifth maiden enters bearing the Gral, whereas in Chretien she is unidentified, Wolfram tells us this is the princess of perfect chastity, Repanse de Schoye, and again as in Chretien, she radiates a brilliant light: “her face shed such refulgence that all imagined it was sunrise.”5

Later, Parzival is told about the Gral, how a warlike company of Templars, the Brotherhod of the Gral, dwell at Munsalvaesche (the Grail Castle). They are nourished from the Stone, the lapsit exillis, who's essence is pure. No matter how ill a mortal may be he cannot die for a week after seeing the Stone. The Gral is nourished by a Dove from heaven on every Good Friday which delivers a small white Wafer to the Stone that it leaves there.6 In a Christian context this may be interpreted as a reference to the former practice of reserving the Blessed Sacrament in dove-shaped receptacles (columb) suspended by chains from the canopy of the altar.

According to Chretien and Wolfram the Grail clearly possesses some religious significance, the procession is an initiation rite, but it is not to linked to the Christian rite of the Eucharist.

The Christianisation of the Grail

Robert de Boron wrote two poems at the beginning of the 13th century; the Joseph d'Arimathe and the Merlin, the latter work surviving only in fragments; the first writer to make a connection between the legend of Joseph of Arimathea and the Matter of Britain. These two works are thought to have formed a greater opus, Le Roman de l'Estoire dou Graal, with the Perceval forming the third and final part. It is likely that de Boron's final work is represented in the Didot Perceval, thought to have been written between 1190 to 1215 AD. The Didot Perceval survives in two quite dissimilar texts in two manuscripts known as the Didot (Paris) and the Modena variants. In both manuscripts containing the prose Perceval it is preceded by a prose version of the poem Joseph d'Arimathie by Robert de Boron and by a prose Merlin, a re-handling of the poem by de Boron. The prose Perceval may be the work of a continuator of the two compositions of Robert de Boron and may bear some resemblance to the lost original.

The Joseph d'Arimathie provides the first history of the Grail but does not mention the bleeding lance but it appears later in the Didot Perceval which follows Chretien in the Grail Procession: “Just as they seated themselves and the first course was brought to them, they saw come from a chamber a damsel very richly dressed who had a towel about her neck and bore in her hands two little silver platters. After her came a youth who bore a lance, and it bled three drops of blood from its head; and they entered into a chamber before Perceval. And after this there came a youth and he bore between his hands the vessel that Our Lord gave to Joseph in the prison...”7

Later in the tale the Fisher King explains the mystery of the Grail to Perceval: “Dear grandson, know that this is the lance with which Longinus struck Jesus Christ on the cross, and this vessel that is called the Grail, know that this is the blood that Joseph caught from His wounds which flowed to the earth....”8

|

| The Attainment of the Grail - Sir Edward Burne-Jones 1895-96 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The supposed ‘ritual uncleanness’ of women during these times led to many prohibitions in Church Law and it was strictly forbidden to have women serving near the altar within the sacred chancel and they were prohibited from entering behind the altar rails during the liturgy. Only men and boys could serve at the altar. The presumed ‘ritual uncleanness’ of women entered Church Law at the time of the flourit of the Grail Romances especially through the Decretum Gratiani (1140 AD), which became official Church law in 1234 AD, a vital part of the Corpus Iuris Canonici and remained in force until 1916.

Women could not distribute communion, teach in church, baptise, wear sacred vestments and they certainly could not touch sacred objects. It was not until 1983 that canon 230 of the Code of Canon Law allowed local ordinaries to permit girls and women to serve the altar and touch sacred objects. If Chretien's grail had been intended as the Chalice of the Last Supper the Grail procession in his tale would have been regarded as Liturgical Abuse. In making the Grail an object of Christian veneration de Boron had no choice but to change the gender of the Gail bearer to a male.

de Boron's work was the inspiration for the Grail Romances that followed and spawned the huge Vulgate Cycle. He was the first author to provide a complete history to the Grail and the first to give a Christian dimension to the legend, relying heavily on the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. According to de Boron, the Grail was the vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper and then used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch the Holy blood at either the Crucifixion or the Deposition. While imprisoned Joseph was sustained by the Grail and the true meaning of the cup was revealed to him by Christ himself. Joseph's family then brought the Grail to the vaus d'Avaron, the valleys of Avaron, in the west, interpreted by later writers as Avalon and subsequently identified with Glastonbury. The mention of Avalon has fuelled the argument that de Boron wrote his work after the monks of Glastonbury had discovered the grave of Arthur and Guinevere in the Abbey grounds in 1191; the inscription on the burial cross confirming that the place was indeed Avalon.9

The legend of Joseph of Arimthaea was generally known at the time with various rhymed French versions in circulation, whereas the Gospel of Nicodemus was used by Gregory of Tours in the 6th century and later translated into Anglo-Saxon, French, English and German in the 12th and 3th centuries.10 Joseph of Arimthaea was particularly venerated at Moyenmoutier in Lorraine in north east France, across the Vosges mountains from Montbeliard and the nearby village of Boron, the apparent birthplace of Robert, which may have influenced his selection of material.11

At one time the Abbey of Moyenmoutier claimed to possess the relics of Joseph of Arimthaea. According to the early 13th century Chronicles of Senones during the time of Charlemagne (king of the Franks 768 - 814 AD), Fortunat, patriarch of Grado, made a pilgrimage to the East and brought back the body of Joseph of Arimathea from the Holy Land to the monastery of Moyenmoutier. At a later date, but before the end of the 10th century, the body of Joseph was taken away by 'strange monks.'12 Although this is a late tradition it may have contributed to the persistence of the Glastonbury tradition whose monks were suspected of the crime.13

In Chretien's story de Boron seems to have recognised elements of the Grail procession as relics of the Passion; the Holy Lance of Loginus and the Chalice bearing Christ's blood as the cup of the Last Supper. Yet it is doubtful that this is what Chretien intended for his unfinished story of the grail. Key to de Boron's thinking must have been the recognition of the Grail Maiden bearing the chalice in the Grail Romances as Ecclesia a figure depicted in Christian iconography as the person holding the chalice and catching the Holy Blood at the Crucifixion in illuminated manuscripts, for which, as we have seen above, he substituted a youth. There is evidence that the Grail legend, at least in the form of the Chalice at the Cross, was known in the Rhine regions from at least the early 6th century.14

The First Grail Maiden

Ecclesia usually appears with Synagoga in Crucifixion scenes from the early 9th century. Ecclesia is shown receiving the Holy blood in the chalice on the 9th century ivory cover to Henry II's early 11th century book of Pericopes. Ecclesia is said to represent the new church as the Virgin, Mary The Church, and is often depicted in Crucifixion scenes with a blindfoled female companion who's head is bowed standing on the opposite side of the cross bearing a broken lance and holding law tablets that are slipping from her grasp. This figure is said to depict Synagoga, the Synagogue, the Jewish Church that turned its back on Christ at the Crucifixion.

|

| Detail from cover of the book of Pericopes 820-830 AD |

The Gellone Sacramentary, dated 790-804 AD, has a Crucifixion scene showing a bleeding Christ without any earthly attendants, a scene which does not appear to have any precedents and was done perhaps to avoid distracting from the scene on the opposite page. This page (folio 144r) represents a head with long hair, forming the top of an initial I for the section of Te igitur that begins Inprimis quae which asks for blessing on the church. In this context the head may represent Ecclesia.

The 8th century Gellone personification seems to be without precedent and predates both the 9th century Utrecht Psalter and the Drogo Sacramentary, the latter showing an unmistakable depiction of Ecclesia catching Christ's blood in a chalice which is possibly the earliest depiction of this theme.

In the Utrecht Psalter depiction of Psalm 115 is the first in the West of Christ hanging dead on the cross. To the left are Mary and John, to the right a mysterious male figure in a loin-cloth holding a paten with bread in his right hand and in his left the chalice held to Christ's side. These images are unique to the Ultrect Psalter, Other psalters of the period such as the Stuttgart Psalter, c.820 AD, do not show this.

The unidentified figure receiving blood in the chalice appears only in the illustration to Psalm 115, folio 67 recto illustrating Psalm 115 verse 4: "I will take the chalice of salvation and I will call upon the name of the Lord" which was recalled during the Mass liturgy. This may be the earliest extant use of this image and earlier than the first depiction of Ecclesia at the Crucifixion scene and is the only scene in the Psalter with an overtly Eucharistic reference, connecting the chalice to the cup of the First Mass.15

It is therefore without doubt that the maiden collecting Christ's blood in a chalice at the Crucifixion is intended as the Chalice of the Eucharist and in this Robert de Boron saw the Grail Maiden of Chretien's Conte du Graal. But what is the significance of the Grail bearer being a virgin?

The Virgin and the Grail

Representations of the Virgin Mary holding a chalice are to be found in the Pyrenees mountains of north west Spain. Some fifty years before Chrétien de Troyes wrote the first known story of the Grail, images of the Virgin Mary with a simple bowl (called a “grail” in local dialect) containing radiant red blood appeared in St Clement, Taull, and eight churches in the Spanish Pyrenees. Historian Joseph Goering argues that they were the original inspiration of the Grail legend, in his view these wall paintings are "the historical origins of the Grail."16

In early 12th century Catalonia the church of St Clement was visited by the master painter who made beautiful frescoes of Christ in Majesty and seated with the apostles is an enigmatic representation of the Virgin Mary holding a Grail, a shallow bowl exuding radiant light, perhaps so hot she covers her hand with her cloak. Other churches in the Catalonia region had similar pictures (and in one case, a damaged statue) with this Grail motif that is found nowhere else in Christendom. The first was commissioned at St Clement in 1123 AD, these paintings bearing testament to the existence a local tradition, or cult, some fifty years before the earliest date for Chretien's Conte du Graal. To add to the mystery of the Grail, in these paintings the lips of the Virgin (Sancta Maria) are shown stitched together as if sealed to safeguard some great secret.17

|

| St Peter (with keys) and St Mary with radiant vessel. Detail from the main apse of St Peter of El Burgal. (Wikimedia Commons) |

In can be of little coincidence that the Grail romances appeared just as Eucharistic devotion was gaining favour at the same time as the recovery of relics of the Passion from the Holy Land became the driving theme of the Crusades.

In addition to its use at the Last Supper, the cup of the First Mass, the Holy Grail was said to have been used to catch the blood of Christ at the Crucifixion. The “Chalice at the Cross” motif that had emerged at the end of the first millennium showing the Chalice in the hands of Ecclesia as the first representation of the Grail Maiden was in existence several hundred years before the first Grail Romances were written.

Copyright © 2014 Edward Watson

http://clasmerdin.blogspot.co.uk

Notes & References

1. William Kibler and Carleton Carroll, trans. Chretien de Troyes: Arthurian Romances, Penguin Classics, 1991.

2. DDR Owen, The Evolution of the Grail Legend, University of St Andrews, 1968.

3. Ibid.

4. Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival, trans. A. Hatto, Penguin Classics, 1980.

5. Ibid p.125.

6. Ibid p.240.

7. Dell Skeels, Didot Perceval or, The Romance of Perceval in Prose: A Translation, University Of Washington Press, 1966. >> Mary Jones Celtic Literature Collective.

8. Ibid.

9. Nigel Bryant, trans. Merlin and the Grail: Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, Perceval: The Trilogy of Arthurian Prose Romances attributed to Robert de Boron, D.S.Brewer, 2008.

10. Emma Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz, The Grail Legend, Princeton University Press, 1998.

11. Ibid.

12. John Matthews, ed. Sources of the Grail: An Anthology, Floris Books, 1996, p.351.

13. Emma Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz, p.344 (fn.15).

14. Linda Malcor, The Chalice at the Cross, 1991.

15. Ian Levy, Gary Macy, Kristen Van Ausdall, editors, A Companion to the Eucharist in the Middle Ages, BRILL, 2011.

16. Joseph Goering, The Virgin and the Grail, Yale, 2005.

17. How else would you paint sealed lips? – see Urgell and the Holy Grail.

18. Goering, op cit.

* * *

.jpg)